Wireless LAN Buyers Guide

I recently went to Fryís to buy more wireless LAN equipment for my home office. With nearly 100 SKUs to choose from, representing each version of the IEEE 802.11 standard known as Wi-Fi, I wondered how consumers might ever make sense of it all. While I pondered my purchase, I overheard two college kids ask a sales associate for help. The sales rep offered some advice, but it was clear that his knowledge was limited, so I introduced myself as a wireless consultant and answered some of their basic questions. Our casual discussion evolved into a 20-minute WLAN course that attracted about a dozen onlookers who also bought wireless products. The father of one young man thanked me for condensing so much information into such a timeframe, and that fun experience convinced me to write this article and explain the tradeoffs that can help you make your own WLAN decisions.

Besides choosing the correct style of adapter for your device (discussed at the end), if you plan to jump on the Wi-Fi bandwagon, you must choose among several 802.11 standards that are evolving at a fast rate and have different features and benefits. The table below gives a quick overview of the tradeoffs, which can change over time. The rest of this article adds detail for each standard and each decision criteria so you can get maximum value from your purchase.

|

T R A D E O F F S |

802.11b |

802.11g |

802.11a |

Dual Band |

|

Frequency Band |

2.4 GHz |

2.4 GHz |

5 GHz |

2.4 & 5 GHz |

Spectrum Allocation |

83.5 MHz |

83.5 MHz |

3001 MHz |

3001 + 82.5 MHz |

Rated Speed2 |

11 Mbps |

54 Mbps |

54 Mbps |

54 Mbps |

Actual Throughput3 |

4.5 Mbps |

7-16 Mbps |

54 / 27 |

54 / 27 |

Range (typical maximum) |

1500' |

200' |

1500' |

1500' |

Reliability (RF Interference) |

usually OK |

usually OK |

much better |

best |

# of Available RF Channels |

11 (3) |

11 (3) |

12 (8)4 |

11 (3) + 12 (8)4 |

Security (encryption) |

48-, 64-, 128-bit WEP |

48-, 64-, 128-bit WEP |

48-, 64-, 128-, 152-bit WEP |

48-, 64-, 128-, 152-bit WEP |

Size / Form Factor |

smallest |

smaller |

smaller |

small |

Battery Life |

best |

better |

often OK |

often OK |

Compatibility |

good |

better |

OK & improving |

best |

Quality of Service |

none |

none |

none |

none |

Ease of Purchase, Setup, Use, Upgrade5 |

varies by |

varies by |

varies by |

varies by |

Investment Protection |

shortest |

long |

long |

longest |

Vendor Brand / Asthetics |

personal |

personal |

personal |

personal |

Street Price6 |

$29/49 |

$39/$69 |

$49/$79 |

$69/$99 |

|

|

|

|

|

NOTES: |

|

|

|

|

1 - Recent

U.N. conference expands allocation to 455 MHz worldwide |

|

|

||

2 -

proprietary turbo modes can double speed to 22 Mbps and 108 Mbps |

|

|||

3 - throughput

decreases with distance as signal strength weakens |

|

|

||

4 - U.N.

conference expands this to 24 channels in U.S. and 19 in Europe |

|

|||

5 - varies

greatly by vendor and application (e.g. SOHO vs. enterprise) |

|

|

||

6 - estimated

retail price after rebate, as of July 2003 |

|

|

|

|

Introduction

Because wireless LANs eliminate Ethernet wiring and add mobility, Wi-Fi networks have exploded into over 11 million U.S. households, according to Gartner Group. Most allow PC users to share a high-speed Internet connection, but Wi-Fi also lets them roam about, moving either from one room to another in the home, or between the home and the office or public hotspot.

Wi-Fi service providers (WISPs) are busy extending broadband Internet access to hotels and conference facilities, airline terminals, coffee shops, and your local McDonalds. Even the ubiquitous pay phone could become an access point, giving you wireless access to DSL connections.

European research firm, ARCChart, predicts there will be over 91,000 of these public hotspots worldwide by the end of 2003 and 203,000 by the end of 2007. And just as with cellular phone networks, WISPs are forming roaming agreements with each other.

The Tradeoffs

As prices fall and the price difference between products using different standards shrinks, price becomes a less important decision criterion. Because itís more important to focus on Value and consider other buying criteria, I will discuss Price as the last of the tradeoffs.

Frequency Band

WLAN products operate in license-free frequency bands at 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz, or a combination of the two. The choice of band is a tradeoff that can affect price, performance, range, and reliability, so consider your application requirements and operating environment.

2.4 GHz Ė The 802.11b and .11g standards use 2.4 GHz, a band that is available worldwide without a license, so products based on these standards are naturally less expensive and more pervasive. If you roam about Ė between homes, offices, and hotspots, or between countries Ė then you may prefer the ubiquity of 2.4 GHz., which also covers longer distances. But 2.4 GHz is prone to RF interference that can slow, or even shut down, a wireless network.

5 GHz Ė The 802.11a standard uses 5 GHz, a band that has more spectrum available for higher performance and is also cleaner with less RF interference. But operating in the 5 GHz band can result in slightly larger and more complex silicon chips, somewhat higher costs, and decreased battery life. So far, products based on this standard are not as pervasive, but this could change as prices fall. If you want to run demanding multimedia applications such as HDTV video streaming, or if you live and work in an environment where RF interference is an issue, then consider 5 GHz.

Multi-mode Ė Canít decide? Why not pay a bit more and buy multi-mode products that operate in either frequency band and can automatically sense and adapt to whatever network is available. Thatís the future, and early products are available today, although at premium prices.

Spectrum Allocation

Regulatory bodies like the FCC allocate radio spectrum (bandwidth) to each type of application, including the unlicensed 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands. Since thereís more bandwidth available at 5 GHz, itís possible to build faster networks in that band.

2.4 GHz Ė 802.11b and .11g are allocated 83.5 MHz of radio spectrum, and this same spectrum is available worldwide. That means companies can make products for global markets, thus driving volumes up and prices down.

5 GHz Ė 802.11a has been allocated more spectrum, with 300 MHz available in the U.S. Thatís why itís faster, and products using this standard can support HDTV video streaming. Actual allocation varies, however, between countries. Since manufacturers currently need different versions of their 802.11a products for different markets, prices are generally higher. Thankfully, delegates at a recent World Radio Communication Conference, which was hosted in June by the U.N., agreed to standardize on spectrum allocation at 5 GHz and increase it to 455 MHz. Once ratified by their respective countries, this will help improve performance and sales volumes, driving prices down.

Rated Speed

Since manufacturers advertise maximum rated speed, most people rely on this as their primary comparison, but it can be misleading. Actual throughput depends on other factors, as described in the next section.

802.11b Ė 11 Mbps is the rated speed of the most popular and mature version of 802.11, which uses DSSS (direct sequence spread spectrum) technology. Some vendors also offer a turbo mode that substitutes PBCC modulation to double that performance to 22 Mbps, but to use these proprietary extensions, you should get all of your network gear from the same manufacturer.

802.11g Ė 54 Mbps is the rated speed of this newer and backward-compatible version of 802.11. To increase performance, .11g uses OFDM (orthogonal frequency division multiplexing) technology instead of DSSS.

802.11a Ė 54 Mbps is the current rated speed, but more should be possible with pending increases in 5 GHz spectrum allocation. Some vendors also offer a turbo mode that uses more RF channels (more bandwidth) to increase performance to 108 Mbps.

Throughput

Because networks have overhead related to software and media access control (MAC), actual throughput is always less than rated speed, and thatís what is important to your applications. A general rule-of-thumb is that throughput is half of rated speed, even with wired Ethernet, but this depends on the amount of overhead imposed.

802.11b Ė Even though the rated speed is 11 Mbps, actual throughput is more like 4.5 Mbps.

802.11g Ė Rated speed is 54 Mbps, but the relatively high overhead of OFDM lowers the maximum throughput to 7-16 Mbps. The slower 7 Mbps speed is due to backwards compatibility features and results when mixing 802.11b and 802.11g devices in the same network.

802.11a Ė Because there is more bandwidth (more channels) available at 5 GHz, 802.11a can achieve a higher maximum throughput of about 27 Mbps, from its 54 Mbps rated speed.

Distance Ė In all cases, throughput diminishes with distance and barriers such as walls that impact signal strength. When pushing their 802.11b products, vendors often cite the longer range of 2.4 GHz products as an advantage over .11a, but remember that .11a starts out faster, so you may still get faster performance throughout your house with .11a.

How much throughput do you need? It depends on your application, and all versions of 802.11 can handle simple needs, including email, printer sharing, Internet access, and even streaming of audio and compressed video. If you want to stream HDTV programs, however, your only choice is 802.11a due to the need for 20 Mbps of throughput. To find out more, refer to my HomeToys article, ďBandwidth: How Much is Needed, and How Much is it Worth?Ē

Range

The same laws of physics affect radio signals and sound, where loudness (signal strength) diminishes with distance and when going through materials like windows and walls. As with sound, radio signals using lower frequencies (2.4 GHz vs. 5 GHz) have less attenuation problems (signal loss) with distance. Likewise, higher frequencies are more able to punch through noisy environments (RF interference).

For sound, this explains why foghorns on ships use low frequencies so they are heard over long distances. And when you pull up next to a teenís car at a stoplight, you may only hear the bass from his sub-woofer. As it turns out, car horns include both a high and low sound Ė one for country driving (long distance) and one for city (punch through traffic noise).

For radio, this explains why the comparison grid shows longer range for products using 2.4 GHz. Note, however, that there are various ways to extend range. The most obvious way is to use more power (shout louder), but regulators limit the amount of transmit power that can used. Other ways to extend range include using more sensitive receivers and high-gain antennas (like hearing aids with the power turned up), directional antennas (like a cheerleaderís megaphone), steerable antennas, repeaters, and mess networks.

For more information on this concept, refer to my HomeToys article on ďWireless in 2003: CES Shows Consumers the Way.Ē

Reliability (RF Interference)

802.11 standards all use digital spread-spectrum technologies to help handle RF interference, but this problem is more severe and difficult to resolve in the crowded 2.4 GHz band, and it can slow down a wireless network or shut it down entirely. Thatís because so many neighboring devices use the same 2.4 GHz band, including nearby WLANs, Bluetooth devices, microwave ovens, some baby monitors, 2.4 GHz cordless phones, and even energy-saving bulbs in stadium lights. Because radio signals can pass through walls, this interference can come from outside and make related network problems difficult to identify.

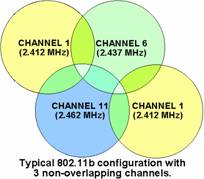

As the WLAN market grows, along with Bluetooth and multi-handset cordless phone markets, RF interference between neighboring apartments, homes, and business offices will become a bigger problem and unavoidable with 802.11b or .11g, which each have only three non-overlapping channels. But as long as you get adequate throughput and the network density in and around your building is not expected to change, 802.11b (or .11g) can be a reliable solution

Over time, however, the market will shift to 802.11a and multi-mode solutions. Thatís because 802.11a is faster, uses the less crowded 5 GHz band, and has more RF channels to choose from (currently 12 in the U.S. and expected to increase to 24), thus making it easier to avoid interference entirely.

Available RF Channels (Non-overlapping Channels)

Available spectrum for wireless networks is divided into different frequency channels, which are set in the access point. Wi-Fi cards then locate the access point with the strongest signal and tune their transceiver to that frequency.

The

cards periodically scan and reattach, allowing them to change channels as they roam about between access points. To minimize RF interference, network administrators set nearby access points to different channels. Both 802.11b

and .11g lets them choose between three non-overlapping channels so they can setup a mini cellular-style network as shown in the illustration.

The

cards periodically scan and reattach, allowing them to change channels as they roam about between access points. To minimize RF interference, network administrators set nearby access points to different channels. Both 802.11b

and .11g lets them choose between three non-overlapping channels so they can setup a mini cellular-style network as shown in the illustration.

Channels can be reused when they are far enough apart, but it takes quite a bit of wireless networking skill to determine the number of access points needed, the distance they should be from each other, and the channels that should be assigned. As a PC user, you shouldnít have to worry about this unless you live in an apartment or home with nearby neighbors that have their own Wi-Fi network.

If you have many neighbors, including ones who live above or below you, you may run out of channels with just three to choose from, and that would be a good reason to choose 802.11a since it offers 8 non-overlapping channels in the U.S. today, with even more planned for the near future. If neighbors arenít an issue, then donít worry about this.

Security (encryption)

Securing wireless networks is difficult since signals go through walls, and most solutions are way too complex for consumers, so they arenít used. Each 802.11 standard includes a basic encryption algorithm called WEP (wired equivalent privacy), but it was never part of the product certification process, so most products ship with WEP turned off. That way, consumers donít need to choose an encryption key, itís easier for them to roam into public hotspots, and the added encryption overhead doesnít slow performance.

For most consumers, basic WEP security is adequate, but you must first turn it on, and itís surprising how many people have never done that. You can increase security beyond basic WEP by choosing a longer encryption key, but for home use, that may not be necessary for two reasons. (1) The information stored there is less valuable to hackers. (2) And the amount of network traffic is much less, so it takes longer to accumulate data enough to break WEP encryption.

For business use, however, WEP is widely criticized as not being secure enough since itís too easy to break. 802.11b defines a 48-bit encryption key, and many manufacturers also support 64- and 128-bit keys. The 802.11a standard goes farther by defining an optional 152-bit key thatís harder to break, and standards groups are working on even more exotic solutions. But since the participants come from large enterprises, the solutions are enterprise-centric, and neither consumers nor small businesses have the network administration skills or the authentication servers required to take advantage of these emerging security standards.

Size / Form Factor

Semiconductors keep getting smaller, which is good since size and weight are especially important to the success of portable devices, especially handhelds. But sometimes to get into a small size, you must give up other things, like larger batteries and antennas. So, thereís a tradeoff.

Products using all popular 802.11 standards are available in the PC Card format for notebook PCs and handhelds, but only 802.11b products are available in the smaller Compact Flash, Secure Digital, and Sony Memory Stick formats. If you want your handheld to have WLAN access, your only choice may be 802.11b. Eventually, weíll see .11a, .11g, and multi-mode products available in these smaller form factors too.

Battery Life

Since portable devices use battery power and are useless when the battery dies, designers must either manage battery life or provide easy ways to recharge. Of the WLAN choices, 802.11b consumes the least amount of battery power, followed by .11g (because of OFDM), .11a (because of OFDM and 5 GHz), and multi-mode.

How important is battery life to you and your applications? If you primarily use a notebook PC to move between different locations and plug in when you get there, itís not an issue. And other factors, besides which version of 802.11 you use, can improve battery life. You can reduce the brightness of your backlit display or change system settings to shut down the disk or cycle back the clock rate during periods of inactivity. Intelís new Pentium M processor, which is part of its Centrino chipset, also contributes to longer battery life.

Compatibility (including Roaming)

Compatibility is not an issue when you buy the same type of network gear from one vendor for use in your home, but it can be a big issue if you use the same PC in your corporate offices or while traveling. Thatís when you must know that your products

are Wi-Fi certified to work with similar products in the same 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz band. ![]()

To make sure that the Wi-Fi products you buy are compatible with those you may find elsewhere in your travels, look for the Wi-Fi compatibility mark but know that it doesnít distinguish between 802.11b, .11g, or .11a, so pay close attention to whatís printed on the box.

Your employer might be using 802.11a because of its faster performance, ability to support more users, and easier network administration, but most of the public hotspots only support 802.11b. And you might think of choosing 802.11g at home for faster performance and backward compatibility with .11b, but consider multi-mode as a way to get the best of all three standards. Since both 802.11a and .11g use OFDM, products with multi-mode radios can easily support both standards.

Quality of Service (QoS)

Quality of Service is not usually an issue for data applications such as email, printing, and Web browsing, since short delays are seldom noticed. Itís critical, however, when transmitting time sensitive information such as voice, audio, and video.

Acceptable performance with those applications requires that data packets arrive on time, and QoS is a measure of how well that is accomplished. QoS is influenced by bandwidth, latency, jitter, and packet error rate.

∑ Bandwidth available for one application can suffer with network congestion other applications that consume bandwidth. Without a way to prioritize traffic, downloading large files can consume so much capacity that thereís not be enough left for video streaming.

∑ Latency is the amount of time between when a packet is sent and received, and delays can be noticed in wireless voice conversations using voice over IP (VoIP).

∑ Jitter is the perceived distortion that results when packets arrive out of sequence or with delays, and it is particularly damaging to multimedia traffic.

∑ Packet Errors are common with RF interference and multi-path reflections, and mechanisms to reduce the packet error rate include automatic error correction and packet retry, but this can cause delays that are noticeable in multimedia applications.

Since Wi-Fi is essentially wireless Ethernet and lacks standards for QoS, some vendors have added their own proprietary QoS technology. The IEEE has started work on a standards-based QoS solution called 802.11e that will eventually make it easier for Wi-Fi to support multimedia applications, even when faced with the challenges mentioned above. I expect 802.11e to be ratified by the end the year. It will take many years, however, for its effect to be felt in the market, since all devices on the network must obey the QoS rules, and if older products donít, then they destroy QoS benefits for all others.

Ease of Purchase, Setup, Use, and Upgrade

Beyond the early adopters, most consumers need products that are easy to buy, install and use, and some vendors do a better job with these issues than others. Microsoft, for example, makes it easy to buy a Wi-Fi network by bundling the networking

components into a kit.  Linksys,

which is also known for easy setup and use, is partnering with Intel to improve that process even more. Future PCs with Intelís Centrino chip will more easily find Linksys access points, and they plan to introduce a ďVerified with Intel Centrino Mobile TechnologyĒ

certification mark, which promises even more than the Wi-Fi mark.

Linksys,

which is also known for easy setup and use, is partnering with Intel to improve that process even more. Future PCs with Intelís Centrino chip will more easily find Linksys access points, and they plan to introduce a ďVerified with Intel Centrino Mobile TechnologyĒ

certification mark, which promises even more than the Wi-Fi mark.

Please donít treat these product mentions as endorsements since many other vendors offer Wi-Fi products designed for consumer markets, with easy setup and use. Possibly a more important characteristic is the ability to apply firmware upgrades to take advantage of future enhancements to security (coming in 802.11i), QoS (in 802.11e), power management (in 802.11h), and other enhancements to the standards. Usually a productís upgrade abilities is described on the box.

Investment Protection

By selecting products that meet both your current and future needs, or that can be enhanced to support them, you help extend the life of your investment, so donít just focus on purchase price.

802.11b is the most popular, most mature, and least expensive wireless standard today, so companies making products based on newer standards bend over backwards to ensure compatibility with that large installed base. By the end of 2004, however, you may not even be able to buy 802.11b products since the newer ones will support .11g, which is backwards compatible, or multi-mode, for both 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz operation. I can make that prediction with confidence because of what happened with Ethernet. Even the cheapest Ethernet products support both 10 and 100 Mbps, and the newest ones are described as 10/100/1000baseT, scaling automatically from 10 Mbps to 1 Gbps. Itís hard to even find a 10baseT product to buy.

Vendor

Brand / Aesthetics

Vendor

Brand / Aesthetics

You might be more comfortable with one trusted brand over another, maybe because of previous experience with wired network products, and thatís OK since itís such a personal choice. Or you might be attracted to one vendorís products because you like their design aesthetics. Thatís OK too and just another tradeoff.

Street Price

You can already get a complete WLAN kit with NIC (network interface card) and AP (access point) for less than $100, and the street prices are falling fast, especially after rebates are applied. With prices this low, there should be no reason to wait, but you may still want to shop around for the best deal. Consider the tradeoffs discussed in this article, however, because the best deal is not necessarily the lowest price. The Tradeoffs grid at the beginning of this article listed some estimated street prices at the time I am writing this, but you may be able to do much better.

What did I end up buying on my trip to Fryís?

Because I live in a 3,000 square foot home in an Austin, Texas neighborhood with small lots and many technologists living nearby, I was concerned with RF interference at 2.4 GHz. There was a good chance that they may have their own WLAN or 2.4 GHz cordless phone system, if not now then sometime later on. So, I specifically looked for 802.11a for its faster speed and its ability to avoid potential interference problems. Instead, I found some dual-band products at a great price after rebate, and I found that they werenít much more expensive than the older 802.11 products.

Hereís what I bought:

∑ Netgear WAB102 Dual-band Wireless Access Point ($129.90 - $50 rebate = $79.90)

∑ Netgear WAB501 802.11 a/b Dual-band Wireless PC Card ($79.90 - $50 rebate = $29.90)

Iíve been quite happy with my purchase. Setup was easy, and I made sure to enable WEP security. Rather than specify a specific frequency, I let the products determine whether itís best to run at 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz, and I let them operate in turbo mode.

I positioned the access point high on a shelf in the home office, which is at the top of the spiral staircase in the middle of the house. PCs in the home office are connected with cat.5 cabling and Ethernet 100baseT. The Netgear Wireless PC Card went into an extra notebook, which I can now use anywhere in and around the house Ė in the living room or family room downstairs, in the master bedroom upstairs, or outside on the deck when the sun isnít so bright that it washes out the screen. In my worst-case scenario, radio signals only have to travel through one floor and one wall with the longest distance being less than 100 feet.

Signal strength has been consistent at about 60% throughout the house, and this gives me about 72 Mbps of transmit performance and 12 Mbps of receive performance. I have had no problems opening my largest PowerPoint presentations (over 30 MB) or streaming video, and Iíve noticed no network degradation due to interference, even with my 2.4 GHz Siemens Gigaset phone and Motorola SimpleFi wireless digital audio receiver, which uses the HomeRF standard at 2.4 GHz.

So to summarize, shop around and compare prices but focus on value and consider other tradeoffs too. You may even want to take this article with you, and potentially share it with the sales rep.

ADDENDUM: The correct adapter for your device

Read this section (or ask the sales person) if you're confused about what type of adapter to buy.

Wi-Fi is getting built in. The newest notebook PCs with Intel's Centrino chipset conserve battery life, include built-in antennas, and have the 802.11b radio already installed. Some vendors use only the Pentium M processor so they can support different wireless standards with a mini-PCI adapter that either comes installed already or is an extra cost option that is best to buy from the PC manufacturer.

PC Card (PCMCIA) adapters. Most notebooks have PC Card slots, so if you're PC isn't preconfigured for wireless, this is what you'll want.

USB adapters. USB is the choice for most desktop PCs. It works with notebooks too, but adds external wires.

PCI adapters. Older desktops without USB slots need internal adapters - usually PCI or the older AT-bus adapters. The disadvantage is that you have to take off the covers and may even have to adjust micro-switch settings.

CompactFlash. Wi-Fi is now available for handhelds in CompactFlash, SD Memory and Sony's Memory Stick formats.

Wireless Router or Access Point. If you have no other home network installed, a wireless router gives several PCs access to the network and lets them share an Internet connection. The wireless router provides router, firewall, and access point functions. If you already have a network with a router and firewall, all you need is an access point, which is normally cheaper.

Repeaters. If you find that range is a problem and you get weak radio signals, consider a repeater. They're available in wireless models that receive and then retransmit signals, or you can buy ones that use existing Ethernet or power line wires as a backbone and can thus extend the range over greater distances.

Of the many other online resources for wireless information, I especially like Intel's site for introductory material.